|

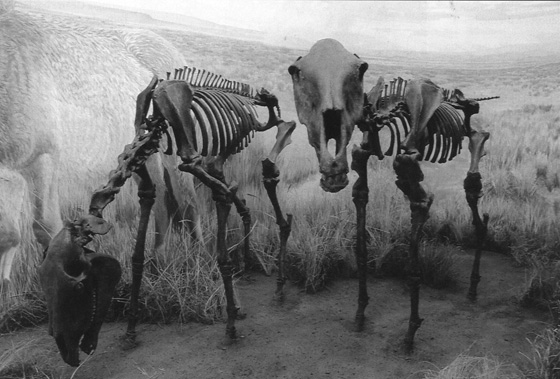

| Photo credit: http://vancouverscape.com/yukon-beringia-interpretive-centre/ |

Before I begin, there are a few things you must understand. First, the modern horse Equus caballos is one of several species under the genus Equus. Equus covers horses, asses (donkeys), and zebras. All three are separate species. Of horses, there are two surviving subspecies: Equus caballos and Equus ferus. The two subspecies are genetically and visibly different from each other, although they can interbreed and produce fertile offspring. Most scientists (and myself) agree that Equus caballos was created through domestication. However, there is also an extinct third subspecies of horse: Equus lambei. Preserved remains of Equus lambei have been discovered and there is no visible difference between it and Equus caballos. Genetic testing has revealed that this horse - which is estimated to have gone extinct 10,000 - 6,000 years ago - is the most recent ancestor of our modern Equus caballos. Where did Equus lambei originate? North America.

In this journal I will discuss the evidence of pre-Columbian equine presence in North America. I will provide a variety and large number of sources for you to explore. There are two prevailing theories: The first is that single-toed horses (caballoid-type horses) never existed in North America at any point in history. The second theory is that Equus caballos appeared on its own and was present in North America until the point when Christopher Columbus sailed in 1492. As you will see, neither theory is correct.

In this journal I will discuss the evidence of pre-Columbian equine presence in North America. I will provide a variety and large number of sources for you to explore. There are two prevailing theories: The first is that single-toed horses (caballoid-type horses) never existed in North America at any point in history. The second theory is that Equus caballos appeared on its own and was present in North America until the point when Christopher Columbus sailed in 1492. As you will see, neither theory is correct.

“The Horse and Burro as Positively Contributing Returned Natives in North America” by Craig C. Downer: article.sciencepublishinggroup…

Craig C. Downer. The Horse and Burro as Positively Contributing Returned Natives in North America. American Journal of Life Sciences. Vol. 2, No. 1, 2014, pp. 5-23. doi: 10.11648/j.ajls.20140201.12

Single-toed horses originated in North America and went extinct around the end of the last Ice Age. Theories of the cause of the extinction include drought, disease, or a result of hunting by humans (early Native Americans). As you will see, the modern horse (Equus caballos) is most likely not native to North America, but evidence suggests that it is not an exotic species. Thus, perhaps the most accurate way to describe E. caballos' relation to North America is "familiar."

Summary of above paper: A common view is that the modern horse species (Equus caballos) is not native to North America and only appeared on the scene 500 years ago, but this article describes how caballoid-type horses are most likely native to North America, and were killed off by humans before being later reintroduced by the Spanish about 500 years ago. The article is written from an evolutionary point of view, but describes various fossils of equines that originated in North America. While the “millions of years” is debatable, the fossils are not. The evidence, including fossils, DNA, an actual frozen Equus lambei dating back 10,000 years, pre-Columbian cave paintings of horses, as well as Chinese writings from over 3,000 years ago describing horses resembling modern Appaloosas, indicates that the equine animal family originated in North America and spread outward, perhaps on ice bridges during the Ice Age (after the Flood, according to a Creationist perspective), or perhaps they were brought to other continents by humans. The Yukon Horse, as Equus lambei became known as, was outwardly identical to Equus caballos (and as ancient writing indicate, behaved identically to Equus caballos) was present in North America approximately 10,000 years ago, which indicates that the horse species originated in North America. The article ends by describing various ways that horses benefit the North American ecosystems.

For those who don't know, Equus lambei is an extinct subspecies of horse that is virtually identical to the modern Equus cabllos, and most biologists agree that Equus caballosis a direct descendant of Equus lambei. As such, the only difference between the modern wild horses living in North America and the ones that died out around 7,500 years ago is a minute DNA discrepancy. In the end, fossils of E. caballos have not yet been discovered in North America, but seeing as they are nearly identical to E. lambei, which is native to North America, then modern horses are actually very familiar to the North American landscape. While not a native subspecies of horse, Equus caballos is not exotic, either.

During the mid-1990s, horse remains were discovered by placer miners in the Yukon. They were well preserved in the permafrost and seemed to have died recently, yet proved to be approximately twenty-five thousand years old. Their rufous color, flaxen mane and solid hooves had the aspect of a typical, small and wiry mustang of the West. Based on external morphology, the specimen was identified as a “Yukon horse,” whose Latin name is Equus lambei. Intrigued, paleontologists conducted a genetic analysis of this specimen, which showed it to be one and the same as the modern horse: Equus caballus. Further independent analysis conclusively proved this. With this substantiation came a more widespread recognition of wild horses as returned native species in North America, since E. lambei was seen to be identical to E. caballus.

Here I came upon some fascinating petroglyphs dating from modern times to a few thousand years ago (Bureau of Land Management, Bishop California office, archeologist, pers. comm.). These artful designs had been painstakingly chiseled with hard tools on granite to form hypnotizing spirals, geometrical checkerboards, arrowheads, lances, strange anthrozooic (man-animal) figures, eagles, bighorn sheep with large, curved horns, and then, much to my amazement, a definite horse figure, without apparent rider, bridle, rope or saddle, rendered in simple rectilinear fashion – but with proportions unmistakably those of a horse. Judging from the brownish oxidation on the chiseling, this horse was not a recent addition to the ancient petroglyphs here. Scientific analysis of the patina of some of these petroglyphs has revealed ages up to 3,000 years. By visually comparing patina hues, I estimated this horse could be well over 1,000 years old.

An intriguing line of evidence that horses were present in America over 3,000 years before Columbus's arrival comes from Chinese writings. One manuscript dating from 2,200 B.C. indicates that the Chinese came to North America by sea at very early dates and described several animals occurring in Fu Sang, or the “Land to the East" [which refers to North America, according to modern cartographers]. Their descriptions match certain North American animals, including bighorn sheep and horses resembling the appaloosa.

While there is still debate over where horses originated, this paper certainly raises interesting questions. I'm curious: what did you think after reading it?

Single-toed horses originated in North America and went extinct around the end of the last Ice Age. Theories of the cause of the extinction include drought, disease, or a result of hunting by humans (early Native Americans). As you will see, the modern horse (Equus caballos) is most likely not native to North America, but evidence suggests that it is not an exotic species. Thus, perhaps the most accurate way to describe E. caballos' relation to North America is "familiar."

Summary of above paper: A common view is that the modern horse species (Equus caballos) is not native to North America and only appeared on the scene 500 years ago, but this article describes how caballoid-type horses are most likely native to North America, and were killed off by humans before being later reintroduced by the Spanish about 500 years ago. The article is written from an evolutionary point of view, but describes various fossils of equines that originated in North America. While the “millions of years” is debatable, the fossils are not. The evidence, including fossils, DNA, an actual frozen Equus lambei dating back 10,000 years, pre-Columbian cave paintings of horses, as well as Chinese writings from over 3,000 years ago describing horses resembling modern Appaloosas, indicates that the equine animal family originated in North America and spread outward, perhaps on ice bridges during the Ice Age (after the Flood, according to a Creationist perspective), or perhaps they were brought to other continents by humans. The Yukon Horse, as Equus lambei became known as, was outwardly identical to Equus caballos (and as ancient writing indicate, behaved identically to Equus caballos) was present in North America approximately 10,000 years ago, which indicates that the horse species originated in North America. The article ends by describing various ways that horses benefit the North American ecosystems.

For those who don't know, Equus lambei is an extinct subspecies of horse that is virtually identical to the modern Equus cabllos, and most biologists agree that Equus caballosis a direct descendant of Equus lambei. As such, the only difference between the modern wild horses living in North America and the ones that died out around 7,500 years ago is a minute DNA discrepancy. In the end, fossils of E. caballos have not yet been discovered in North America, but seeing as they are nearly identical to E. lambei, which is native to North America, then modern horses are actually very familiar to the North American landscape. While not a native subspecies of horse, Equus caballos is not exotic, either.

Craige C. Downer is a wildlife ecologist who specializes on Perissodactyl mammals: www.coasttocoastam.com/guest/d…, andeantapirfund.com/CraigCDown…, and is clearly qualified to write scientific articles: equinewelfarealliance.org/uplo…, academic.research.microsoft.co…

UPDATE #1: It has been brought to my attention that one of my incessant stalkers on here has been making Ad Hominem claims against Science Publishing Group in an attempt to discredit this article. Aside from the fact that the article was written by Craige C. Downer for the American Journal of Life Sciences (more information above) and not by or for Science Publishing Group, Ad Hominem attacks are a logical fallacy and therefore suggest that this individual is desperate. On top of that, this person's claims against Science Publishing Group (SPG) are baseless. I have looked into SPG myself, and they are merely an outlet for scientists of all fields to publish papers. They have no overarching worldview or agenda, other than to let scientists speak up. There are no scams or viruses on their homepage, as my stalker claims there are: www.sciencepublishinggroup.com… . They answer their phone. They answer their e-mail. Everything you need to contact them is literally at the bottom of their homepage, where one would expect it to be. Their unsubscribe button works. It leads to this page right here: www.sciencepub123.com/unsubscr…. She even went so far as to say that SPG is predatory. Either my stalker is mistaking Science Publishing Group for a different organization, or she is deliberately deceiving her audience. What's perhaps the most obvious, however, is how she claimed that mitochondrial DNA testing is not reliable, even though she has used it many times to make points about how wolves should be eradicated from various parts of North and South America. Convenient how she'll rely on mitochondrial DNA testing when it agrees with her points, but suddenly turns her back on it when it implies that she's wrong. She also mistakenly assumed that the paper was written by Jay F. Kirkpatrick, which implies that she didn't even read it. Even more so, she says my sources are unavailable, even though they are...right here on this page. She finishes off by describing all of the worst-case problems that wild horses have supposedly caused, even though those problems were actually caused cases of extreme mismanagement of wild horses but principally by cattle. (She's under the impression that cattle are not allowed on HMAs, but that's not true; check out the last two questions and answers on this page: www.blm.gov/nv/st/en/prog/wh_b…). While it's undeniable that overpopulated horses cause environmental damage, horses in healthy populations actually benefit the land in many ways, as Craige C. Downer described. They're like any animal: when in unnatural populations, they're damaging, but not when they're in healthy populations. All of these Ad Hominem attacks, convenient changes of mind, and baseless/nonsensical accusations, all just go to show how far anti-Mustang people will go to justify their hatred and and personal vendettas against mere animals.

UPDATE #2: My stalker has once again used more Ad Hominem attacks and irrelevant information to attempt to explain away Equus lambei's presence in North America. She says the article I linked to is not from a scientific journal. Not only is that Ad Hominem and a logical fallacy, but it's also false. It's from the American Journal of Life Sciences. She conveniently ignores this and focuses on the online publication source, which is irrelevant. She also seems to have difficulty following citations, because the paper's sources are quite easy to find. She is also free to contact Craige C. Downer himself for direct access to his sources (his contact information is at the beginning of his paper.) But I have a feeling she'd rather write rants on DeviantART rather than actually talk to an expert. She continued on to pick fun at cave paintings of animals that resemble horses, saying that they're "obviously" mountain lions (ancient mountain lions must have had really long necks...) What's ironic, though, is how she herself admits that cave painting interpretations are subjective. We both agree that the real evidence lies in the fossils and preserved remains of E. lambei, which she tries to explain away by erroneously comparing E. lambei and E. caballos to dogs and wolves (more about that further on). She also seems to have missed the entire point of the paper I linked to as well as my point: we don't know for sure where Equus caballos (modern horse) originated, but we know that Equus lambei originated in North America, and since DNA testing has revealed that E. caballos is nearly identical to E. lambei, it stands to reason that the two are closely linked. This would mean that caballoid-type horses (single-toed, long-maned, long-tailed horses) were present in North America as late as 7,600 years ago. To deny this is to remain willfully ignorant, as the skeleton and pelt of the animal in question is documented and one specimen is on display in Canadian museums. You can see it with your own eyes. I won't even bother to address her ridiculous claim that the Yukon horse is fabrication. I don't have time for such nonsense. The question is now this: how related is E. lambei to E. caballos? According to mitochondrial DNA testing, they are virtually identical. Unlike dogs and wolves, there is almost no difference genetically or visibly. They are more like Siberian tigers vs. Bengal tigers than dogs vs. wolves (Siberian tigers and Bengal tigers are both subspecies of the Tigris genus, just like how Equus caballos and Equus lambei are both subspecies of the Equus genus.) My stalker attempts to explain this away by claiming that mtDNA testing is unreliable. However, as I mentioned above, she relies on mtDNA testing frequently to make claims about how various species of wolves are not the original native subspecies of various areas of North and South America. If she believes mtDNA testing is reliable when it supports her beliefs, how come it's suddenly not reliable when it contradicts her? This kind of selective logic is extremely unscientific.

In the end, she's once again letting hatred and emotion get in the way of scientific reason. She's making strawmen out of my arguments: I am not saying that Mustangs are a native species or that they should go un-managed. Unlike her, I'm open to the fact that there is debate in the scientific community about the native status of E. caballos to North America. We both agree that the Yukon Horse (E. lambei) is not an E. caballos (Mustang). We both agree that Mustangs should be managed. Where we disagree is how they should be managed. She believes that single-toed horses are an "exotic" species to North America (therefore ignoring the fossil evidence) and thus should be completely eradicated, even though that would not solve the habitat degradation problem. I believe that single-toed horses existed in North America as recently as 7,600 years ago (seeing as we have fossils of them), and while those horses were not E. caballos, they are the ancestor of E. caballos, and thus modern horses are not as "exotic" as one would think. However, seeing as humans hunt horses' natural predators and use the land for cattle grazing (blaming the environmental damage caused by their cattle on the horses), the horses need to be managed. We can't expect people to go hungry for the sake of animals. Mustangs don't need to be eradicated, but they do need to be managed. In the end, I don't believe Equus caballos is native to North America, there is no denying that it is familiar. It's not a native subspecies to North America and I never claimed that it was, but it is not the exotic animal that this hater makes it out to be.

I will not be responding to any further of her strawman "responses," threats, or immature jabs at my intelligence because A) they're not worth my time, and B) she's a stalker.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

More information about the possibility of equines being familiar to the North American landscape:

www.thecloudfoundation.org/ima…

I phoned Dr. Gotthardt, and she explained how she had immediately flown north to Dawson City to investigate the land. As she hiked into Last Chance Creek canyon, the stench of rotting flesh greeted her long before she saw the partial body of a horse jutting out of the canyon wall above. Initially she believed the miners had unearthed a contemporary horse. Beyond the smell, it had all the characteristics of a contemporary horse - solid hooves and a brown coat with a flop-over, blondish mane. But, when the carcass was radiocarbon dated, it turned out to be 26,000 years old!

Equus lambei is the link between our contemporary wild horse (currently roaming in remnant herds across 10 western states), and the horses that died out as recently as 7,600 years ago. Both are caballoid-type horses - Equus Caballus, the modern horse. The Yukon Horse confirms that the horses that died out on this continent arevirtually the same as the ones that returned with the Spanish Conquistadors in the early 1500s and eventually escaped to reclaim their freedom.

A growing number of scientists are acknowledging the mustang as a returned native species, not the least of whom is the Curator of the Division of Vertebrate Zoology at the American Museum of Natural History, Ross MacPhee, PhD. He states, "The contemporary wild horse in the United States is recently derived from lines domesticated in Europe and Asia. But those lines themselves go much further back in time, and converge on populations that lived in North America during the latter part of the Pleistocene (2.5M to 10k years ago)." Dr. MacPhee refers to this re-introduction as, biologically speaking, Aa non-event: horses were merely returned to part of their former native range, where they have since prospered because ecologically they never left.

"Scientists know from fossil remains that the horse originated and evolved in North America, and that these small 12 to 13 hand horses or ponys (sic) migrated to Asia across the Bering Strait, then spread throughout Asia and finally reached Europe. The drawings in the French Laseaux caves, dating about 10,000 B.C., are a testimony to their long westward migration. Scientists contend, however, that the aboriginal horse became extinct in North America during what is (known) as the “Pleistocene kill,” in other words, that they disappeared at the same time as the mammoth, the ground sloth, and other Ice Age mammals." -PRESENTED BY Claire Henderson, Laval University, Quebec, Canada. 2-1-91. IN SUPPORT OF SENATE BILL 2278 (North Dakota)

STATEMENT OF CLAIRE HENDERSON

HISTORY DEPARTMENT

BATIMENT DE KONINCK

LAVAL UNIVERSITY

QUEBEC CITY, QUEBEC CANADA

236 Rve Lavergne Quebec, Quebec, G1K-2k2 Canada

418-647-1032

It’s generally accepted that [the] horse species evolved on the North American continent. The fossil record for equine-like species goes back nearly 4 million years. Modern horses evolved in North America about 1.7 million years ago, according to researchers at Uppsala University, who studied equine DNA. Scientists say North American horses died out between 13,000 and 10,000 years ago, at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, after the species had spread to Asia, Europe, and Africa.

Horses were reintroduced by the Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Animals that subsequently escaped or were let loose from human captivity are the ancestors of the wild herds that roam public lands today.

The submergence of the Bering land bridge prevented any return migration from Asia [which is why horses did not reappear until the Spanish brought them over.] There’s no proof any horses escaped extinction in the Americas. If horses survived in the New World up to the 15th century, then no one has ever been able to find the physical evidence to prove the theory.

Many scientists once thought horses died out on the continent before the arrival of the ancestors of the American Indians, but archeologists have found equine and human bones together at sites dating back to more than 10,000 years ago. The horse bones had butchering marks, indicating the animals were eaten by people, according to “Horses and Humans: The Evolution of Human-Equine Relationships,” edited by Sandra L. Olsen.

The horses were “reintroduced” to the continent [North America], unlike the Asian clams in Tahoe or the rabbits of Australia, which were inserted into regions where Nature never put them and where they could disrupt the ecological balance.

The evidence thus favors the view that this species is "native" to North America, given any rational understanding of the term "native". By contrast, there are no paleontological or genetic grounds for concluding that it is native to any other continent.

-Ross MacPhee, PhD

www.horsetalk.co.nz/news/2009/… and www.thecloudfoundation.org/edu…

Researchers who removed ancient DNA of horses and mammoths from permanently frozen soil in central Alaskan permafrost dated the material at between 7600 and 10,500 years old.

Some large species such as the horse became extinct in North America but persisted in small populations elsewhere, having crossed a land bridge into Asia.

But one core, deposited between 7,600 and 10,500 years ago, confirmed the presence of both mammoth and horse DNA. To make certain that the integrity of this sample had not been compromised by geologic processes (for example, that ancient DNA had not blown into the surface soils), the team did extensive surface sampling in the vicinity of Stevens Village. No DNA evidence of mammoth, horse, or other extinct species was found in modern samples, a result that supports previous studies which have shown that DNA degrades rapidly when exposed to sunlight and various chemical reactions.

www.horsetalk.co.nz/news/2009/…

Miners Sam and Lee Olynyk, and Ron Toews, who were working a claim in the Klondike, found the remains in September 1993. It has since been identified as a horsewhich once roamed the plains of the area and has been radiocarbon dated at 26,000 years old.

www.horsetalk.co.nz/features/n… , www.thecloudfoundation.org/edu…

byJay F. Kirkpatrick, Ph.D. andPatricia M. Fazio, Ph.D. Also available here: ispmb.org/WildHorsesInAmerica.…

The precise date of origin for the genus Equus is unknown, but evidence documents the dispersal of Equus from North America to Eurasia approximately 2-3 million years ago and a possible origin at about 3.4-3.9 million years ago. Following this original emigration, several extinctions occurred in North America, with additional migrations to Asia (presumably across the Bering Land Bridge), and return migrations back to North America, over time. The last North American extinction probably occurred between 13,000 and 11,000 years ago (Fazio 1995), although more recent extinctions for horses have been suggested. Dr. Ross MacPhee, Curator of Mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History, and colleagues, have dated the existence of woolly mammoths and horses in North America to as recent as 7,600 years ago. Had it not been for previous westward migration, over the 2 Bering Land Bridge, into northwestern Russia (Siberia) and Asia, the horse would have faced complete extinction. However, Equus survived and spread to all continents of the globe, except Australia and Antarctica.

Thus, based on a great deal of paleontological data, the origin of E. caballus is thought to be about two million years ago, and it originated in North America.

Not only is E. caballus genetically equivalent to E. lambei, but no evidence exists for the origin of E. caballus anywhere except North America (Forstén 1992).

The issue of feralization and the use of the word "feral" is a human construct that has little biological meaning except in transitory behavior, usually forced on the animal in some manner. Consider this parallel: E. Przewalskii (Mongolian wild horse) disappeared from Mongolia a hundred years ago. It has survived since then in zoos. That is not domestication in the classic sense, but it is captivity, with keepers providing food and veterinarians providing health care. Then they were released during the 1990s and now repopulate their native range in Mongolia. Are they a reintroduced native species or not? And what is the difference between them [E. Przewalskii] and E. caballus in North America, except for the time frame and degree of captivity?

STATEMENT OF CLAIRE HENDERSON

HISTORY DEPARTMENT

BATIMENT DE KONINCK

LAVAL UNIVERSITY

QUEBEC CITY, QUEBEC CANADA

236 Rve Lavergne Quebec, Quebec, G1K-2k2 Canada

418-647-1032

Horses were reintroduced by the Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Animals that subsequently escaped or were let loose from human captivity are the ancestors of the wild herds that roam public lands today.

No comments:

Post a Comment